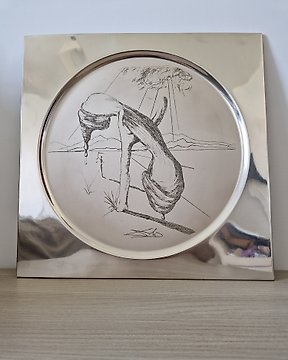

Piatto Da esposizione serigrafia Argento 925 (1) - Argento - Salvador D'ali - Italia - 21° secolo

N. 39474815

N. 39474815

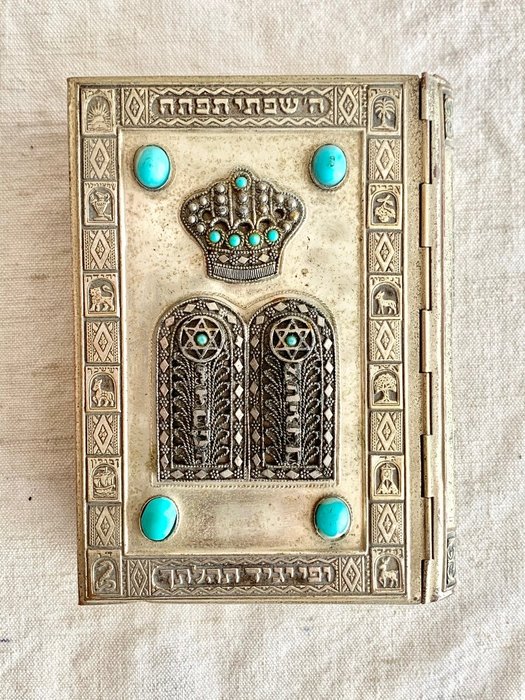

Judaica - A magnificent Jewish prayer book with A silver plated binding / cover

Unique cover / binding - rich with Jewish motives - ten commandment - holy places in israel - ten tribes

Mounted with turquoise stones

Good used vintage condition

Please notice book shows signs of wear and aging

Hand crafted by an Israeli artist - 1950

Jewish prayer (Hebrew: תְּפִלָּה, tefillah [tfiˈla]; plural תְּפִלּוֹת tefillot [tfiˈlot]; Yiddish: תּפֿלה, romanized: tfile [ˈtfɪlə], plural תּפֿלות tfilles [ˈtfɪləs]; Yinglish: davening /ˈdɑːvənɪŋ/ from Yiddish דאַוון davn 'pray') is the prayer recitations and Jewish meditation traditions that form part of the observance of Rabbinic Judaism. These prayers, often with instructions and commentary, are found in the siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer book. However, the term tefillah as referenced in the Talmud refers specifically to the Shemoneh Esreh.

Prayer—as a "service of the heart"—is in principle a Torah-based commandment.[1] It is not time-dependent and is mandatory for both Jewish men and women.[2]

You shall serve God with your whole heart.

— Deuteronomy 11:13

However, in general, today, Jewish men are obligated to conduct tefillah ("prayer") three times a day within specific time ranges (zmanim), while, according to some poskim ("Jewish legal authorities"), women are only required to engage in tefillah once a day, others say at least twice a day.[3]

Traditionally, since the Second Temple period, three prayer services are recited daily:

Morning prayer: Shacharit or Shaharit (שַחֲרִת), from the Hebrew shachar or shahar (שַחָר) "morning light",

Afternoon prayer: Mincha or Minha (מִנְחָה), the afternoon prayers named for the flour offering that accompanied sacrifices at the Temple in Jerusalem,

Evening prayer:[4] Arvit (עַרְבִית, "of the evening") or Maariv (מַעֲרִיב, "bringing on night"), from "nightfall".

Further additional prayers:

Musaf (מוּסָף, "additional") are recited by Orthodox and Conservative congregations on Shabbat, major Jewish holidays (including Chol HaMoed), and Rosh Chodesh.

A fifth prayer service, Ne'ila (נְעִילָה, "closing"), is recited only on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

The Talmud Bavli gives two reasons why there are three basic prayers de-rabbanan ("from our Rabbis") since the early Second Temple period on: to recall the daily sacrifices at the Temple in Jerusalem, and/or because each of the Patriarchs instituted one prayer: Abraham the morning, Isaac the afternoon and Jacob the evening prayer. [5] The Talmud yerushalmi states that the Anshei Knesset HaGedola ("The Men of the Great Assembly") learned and understood the beneficial concept of regular daily prayer from personal habits of the forefathers (avoth, Avraham, Isaac, Yaacov) as hinted in the Tanach, and instituted the three daily prayers.[6] A distinction is made between individual prayer and communal prayer, which requires a quorum known as a minyan, with communal prayer being preferable as it permits the inclusion of prayers that otherwise would be omitted.

Maimonides (1135–1204 CE) relates that until the Babylonian exile (586 BCE), all Jews had composed their own prayers, but thereafter the sages of the Great Assembly in the early Second Temple period composed the main portions of the siddur.[7] Modern scholarship dating from the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement of 19th-century Germany, as well as textual analysis influenced by the 20th-century discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, suggests that dating from this period there existed "liturgical formulations of a communal nature designated for particular occasions and conducted in a centre totally independent of Jerusalem and the Temple, making use of terminology and theological concepts that were later to become dominant in Jewish and, in some cases, Christian prayer."[8] The language of the prayers, while clearly from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE),[9] often employs Biblical idiom. Jewish prayerbooks emerged during the early Middle Ages during the period of the Geonim of Babylonia (6th–11th centuries CE)[10]

Over the last two thousand years traditional variations have emerged among the traditional liturgical customs of different Jewish communities, such as Ashkenazic, Sephardic, Yemenite, Eretz Yisrael and others, or rather recent liturgical inventions such as Hassidic, and Chabad. However the differences are minor compared with the commonalities. Most of the Jewish liturgy is sung or chanted with traditional melodies or trope. Synagogues may designate or employ a professional or lay hazzan (cantor) for the purpose of leading the congregation in prayer, especially on Shabbat or holidays.

Come fare acquisti su Catawiki

1. Scopri oggetti speciali

2. Fai l’offerta più alta

3. Paga in tutta sicurezza